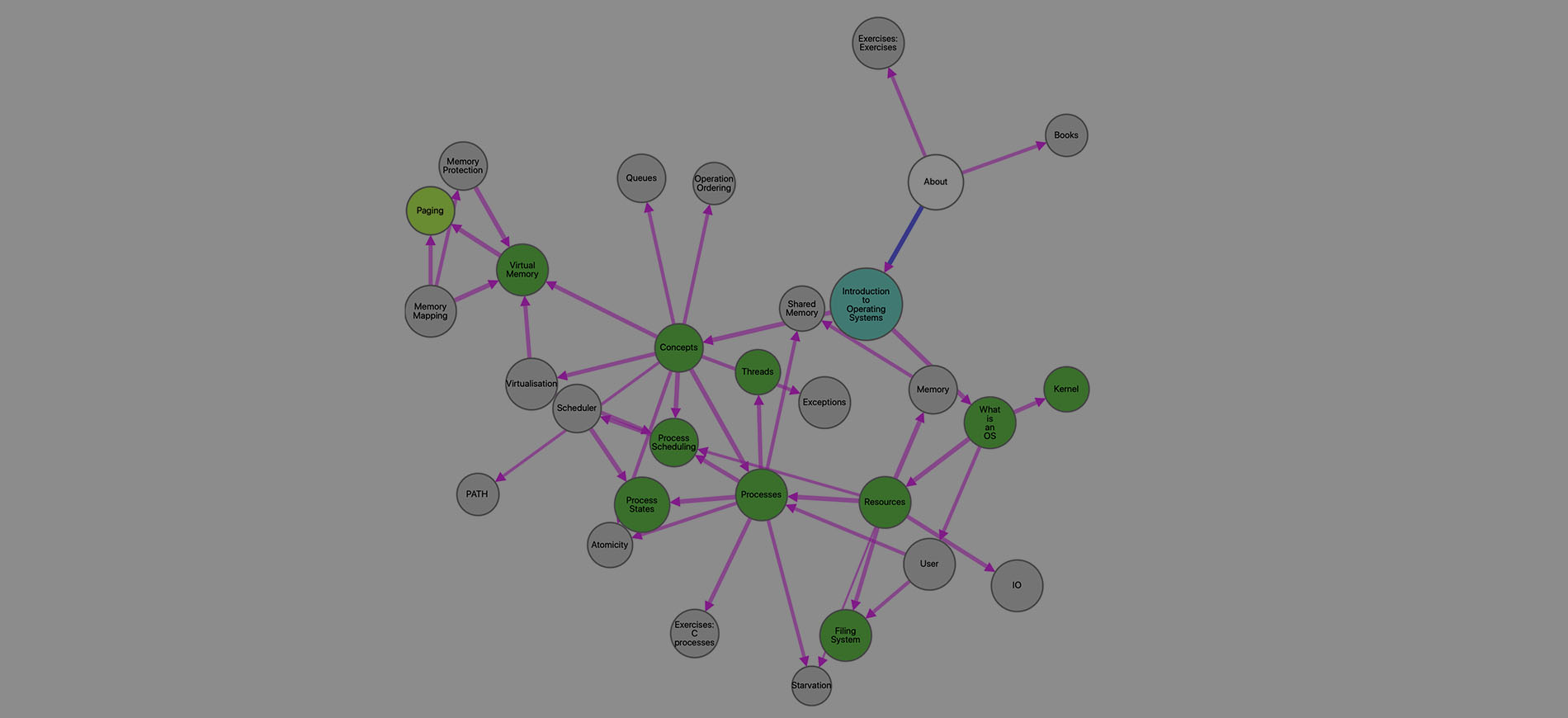

Ch0 Intro

0. Brief explaination of OS and what this unit will cover

In a single sentence, an operating system is the abstraction layer between user software and the physical computer hardware.

The objectives of the operating system are to provide a simplified, regular interface to resources such as data files (regardless of where or how they are stored) and to isolate the application from anything else which the computer might be doing.

Underneath all of this, the operating system manages the available resources in an attempt to give the best user service. Resources include such things as:

- Processing time

- Memory

- Files

- Input and Output (IO) devices

This course unit will cover four broad areas which are core operating systems topics:

- Memory Management:

allocating, maintaining and protecting the computer’s RAM - Process management:

with a focus on multi-tasking and process scheduling. - File management:

more on ‘permanent’ storage and access. - Device management:

dealing with input/output and communications.

1. Formal definition of OS and its main functionalities

Definition: Operating System

An operating system is a layer of software which lies between the application(s) program(s) and the hardware.

In a “primitive”, single-tasking system this may provide just an abstraction layer, allowing the same applications to run on different hardware.

In more complex systems, it provides more services, allowing multiple applications to run ‘simultaneously’. This requires a degree of resource management.

1.1 OS properties

Modern operating system usually share the following properties:

-

Protection

An operating system typically offers some added security to a system.

At its simplest, this might be that difficult-to-write code – such as that needed to communicate with various hardware peripherals – is already provided.

More sophisticated systems are able to prevent unauthorised access. -

Multi-tasking

Multi-tasking systems are those which can run multiple, non-interacting applications simultaneously.

In particular it is able to schedule the software in conjunction with the hardware to gain better efficiency. -

Multi-user

A simple multi-tasking system may still ‘belong’ to a single user. Historically, once multi-tasking was common it was frequently desirable to share the expensive computer time amongst many users simultaneously.

This introduced the need for further security measures, protecting users from each other whilst allowing sharing when appropriate.

1.2 OS kinds

There are three main kinds of OS:

- Monolithic:

By far the most common organization, in the monolithic approach the entire operating system runs as a single program in kernel mode. - Layered Systems:

Layers selected so each only uses functions, operations & services of lower layers. Lower layers (“kernel”) contain most fundamental functions to manage resources. - Microkernels:

Keep only minimal functionality in the OS.

The kernel is the core of an operating system: the part which resides in protected space, including the process manager, scheduler, interprocess communication, exception handlers, resource managers etc.

It is isolated from the user space (assuming the processor/system architecture allows this – most ‘large’ systems do, these days) and connected by system calls.

The kernel is responsible for implementing mechanisms; the debate is whether it should also be responsible for policy. Time for an example:

- A scheduling mechanism includes the code which saves the context of one process and restores the context of another. It may be highly specific to a particular processor ISA.

- A scheduling policy is responsible for when to switch: decisions on time-slicing, priority etc. This is generally fairly processor-agnostic.

Similar examples can be constructed for memory management, filing systems etc.

- Monilithic Kernel:

Everything is included in the kernel and runs in the privileged mode. All the routines have direct access to the operating system’s memory.

Disadvantages:- Size: code continues to ‘bloat’ as it develops which makes management difficult.

- Reliability: an introduced bug in one place can crash the whole system.

- Portability: it is harder to adapt a large slab of code for a new system/architecture.

- MicroKernel:

The kernel contains the handlers which need to be privileged but functions which do not. Examples might include the filing system, graphical user interface (GUI) and device drivers – are separated as user-mode processes.

This keeps the size of the ‘sensitive’ code down, which is likely to improve reliability as it’s easier to modify and maintain. Only the required device drivers need to be loaded and a fault in one of these (a likely source of problems) cannot crash the kernel itself.

Disadvantages:- Speed: the additional needs for communications (and extra system calls) leads to a greater overhead from the O.S.

- Complexity: greater complexity gives more potential for problems.

1.3 OS Resource Management

An important function of an operating system is resource management.

The resources of the system are the things it has or may do, and these need to be managed – and sometimes rationed – amongst the competing demands of users.

Examples of what may be considered as resources:

Processing time

A computer will have one or more processors . Every computation takes some time.

At a particular moment it is not unusual to want to do more computation than is possible; at other times there may be nothing to do.

A typical operating system will share processing time as fairly as it knows how to try to provide a good service for competing demands.

Modern systems may have several processor ‘cores’. In addition, there may be other processing resources – such as a GPU.

What ‘best’ is may depend on circumstances. In a real-time system, response time may be fairly obvious; with an interactive user ‘not obviously slow’ may be good enough; when calculating big computing loads, concentrating on a single job at any time may maximise efficiency.

Memory

Any computer has a certain amount of storage for keeping its programs and data, which must be shared amongst competing demands.

There are various techniques which allow the machine to appear to have more memory than it actually does, so the memory resource can be better exploited. This memory management is done by the operating system.

- Address space

The space where your code and variables might be is a related resource but it is slightly different from the memory which is in use. This, too, can be a precious resource. An operating system may allocate address space (the potential to use memory) but not give any real physical memory until and unless it gets used.

Files

Files are available to different software and sometimes, but not always, different people. Something has to manage this.

What happens if two people or programs try to write to the same file at the same time? What if someone tries to delete a file which is currently being used?

This is all managed by the filing system, which is part of the operating system resource management.

Interfaces

A computer’s I/O usually involves many different I/O devices. Programming every device in every application would be difficult. Usually an operating system tries to make devices look as similar to each other as is sensible which, in turn allows facilities such as redirecting your output from the screen to a file, or a printer with minimal difficulty.

It is also necessary to manage devices.

Keeping track

Users are often badly behaved. Fortunately in most cases the operating system is allocating the resources and can track who-owns-what. It is then possible to check this information when a process dies and recycle the resources appropriately. This can be a particular issue if the process is terminated abnormally, e.g. via a SIGINT type of exception.

Nevertheless, shutting down processes tidily is encouraged and ought to be given some consideration.

Some resources are “pre-emptable”: even if they have been granted they can be put aside without harm. Two obvious examples are processing time (suspend a process and context switch) and, in some systems, memory (page swap onto secondary store).

“Non-pre-emptable” resources – such as a printer in the middle of a print-job – must not be interrupted and the resource must be requested, locked and subsequently released. Careless use of non-pre-emptable resources is a source of deadlock.