Ch1 Memory Management

We now look at the software tasks involved in managing memory as a resource:

1. Definitions & Properties of Memory

Definition: Memory

Computers hold data in a memory which is a large array of equal-sized storage spaces.

Each location has its own identifier: this is usually expressed as a hexadecimal number. This is the address of the location.

Inside the store is a value which is the data. The data can represent whatever you choose it to represent.

The size of the virtual address space of a particular computer processor is fixed by the architecture of that processor.

Because artificial computers are almost all digital, binary systems, the size is a typically a power of two – and most likely a power of (a power of 2).

$16$-bit spaces with $2^{16}$ = $64$Ki = $65,536$ locations

$32$-bit spaces with $2^{32}$ = $4$Gi = $4,294,967,296$ locations

$64$-bit spaces with $2^{64}$ = $16$Ei = $18,446,744,073,709,551,616$locations

2. Managing the memory

Definition: Memory Management

In a simple system without virtual memory, as one process uses up some proportion of the memory it becomes unavailable for others.

With virtual memory and paging some of the restrictions can be bypassed (up to a point) but the problems still arise.

Any process will require one or more logical memory segments. (contiguous parts of the address space). Therefore, memory, as one subclass of Resources, should be allocated, managed and controlled. This is done via Memory Management.

Memory management can be done by both the application and the OS. Sometimes an application will request large blocks of memory and then allocate from them to save some (expensive) system calls.

However in the end it is the OS which is responsible for the memory as a resource.

The O.S. may need to: (The Context of Memory Management)

- allocate spaces when a process is loaded

- set up pages in a virtual memory system

- manage access permissions

- allocate additional space if the stack or heap overflow

- keep track of a process’ use and recover the resource when the process terminates.

2.1 Memory Mapping

Definition: Virtual Memory

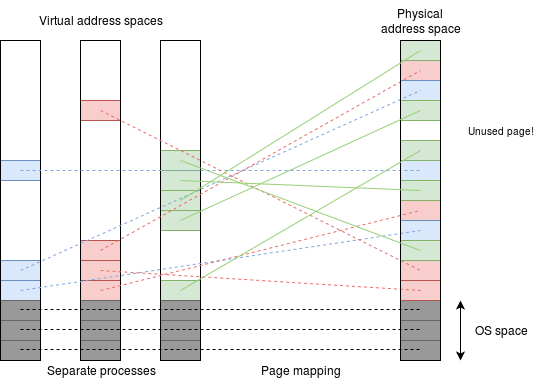

In a virtual memory system, a process’ address is referred to as a virtual address: this is translated to a physical address such that each physical location has a single correspondence with a process-plus-virtual-address combination.

Different machines may have different amounts of physical memory installed. However, in a virtual memory system the application can simply assume that ’all’ the memory – the amount being set by the virtual machine size – is present and it can use any which it wants.

This is also independent of other applications which may be running concurrently.

To achieve this, each process has a private map which translates the virtual addresses, which the application generates, into non-conflicting physical addresses. This solves any potential address address conflicts.

Then how to implement memory mapping? We have the following observations:

- Very few processes use the whole of their virtual address space.

- It may be hard to predict which virtual addresses a given process chooses to use.

- There is typically significant locality of access: if one address is used it is likely that addresses around it are also used.

These properties are therefore exploited when memory mapping virtual to physical addresses, a process usually called address translation.

Definition: Address Translation

Address translation is a process to translate addresses from a virtual address space (the addresses the application is aware of) to a physical address which the memory hardware deals with.

Notes:

- Addresses are not translated individually: they are organised into pages which share a translation. This keeps the size of the tables manageable.

- The most significant bits of the address are used to define the page number. Only the page number is translated.

- It is possible to alias more than one virtual page to the same physical page.

- Not all virtual pages need an allocation of physical RAM. A page can be marked as ‘invalid’ if it is not wanted.

- The page table may have some ‘spare’ bits which can be used for other purposes.

2.2 Memory Paging & Segmentation

Definition: Memory Segmentation

The memory is divided logically into a number of regions in any given application. The parts of memory grouped together in these logical divisions are typically referred to as segments.

The process of dividing and grouping memory into segments is called Memory Segmentation.

Notes:

- A particular segment will have a set of attributes (such as can or cannot be written to) and different segments will have different attributes.

- There can be an arbitrary number of segments and they will typically have different sizes.

- The logical segment will typically be mapped using hardware pages and the pages will be organised by software.

Question:

can you spot any advantages in using paging hardware over trying to map variable-sized segments into RAM?

Answer:

Mapping a segment using page tables is more expensive than having a single mapping entry for the segment, but it brings a couple of useful advantages.

- Because each page can be mapped individually, the segment does not need a (possibly, large) contiguous space in the physical memory. The pages can be used to fragment the segment. This gives much more flexibility and (largely) overcomes the problem of having enough memory in total to accommodate another segment, but not enough in one place.

- By implication, if necessary a logical segment can be increased in size whilst the program is running without worrying about overlapping other memory. This could happen if, for example, more memory was being demanded for the stack or the heap.

- With virtual memory only some of the pages in a segment – those which are actually in use – need be present in physical memory at any time.

- As an example, consider a code segment. In any given run, quite a lot of the code may never be needed: for example code to handle errors is important to have, but rarely executes. With paging and virtual memory, unwanted code (or data) need not occupy valuable physical memory as it is only fetched if it is needed.

Definition: Memory Pages

A page is a division of a virtual memory system (a fixed size block of memory). The whole address space is sliced into pages which – for implementation purposes – will each contain 2N locations.

The page is an indivisible block. The operating system will assign memory to a process in pages: thus a program which has (say) 14 KiB of code will have four pages in which that code will be stored.

Definition: Page look-up

The processor produces a virtual address from which the MMU looks up a page reference. If the page is present in physical memory the translated (physical) address is passed on and everything just works. The look-up is all done by the MMU hardware so this can all run as part of a user’s application process.

Definition: Page faults

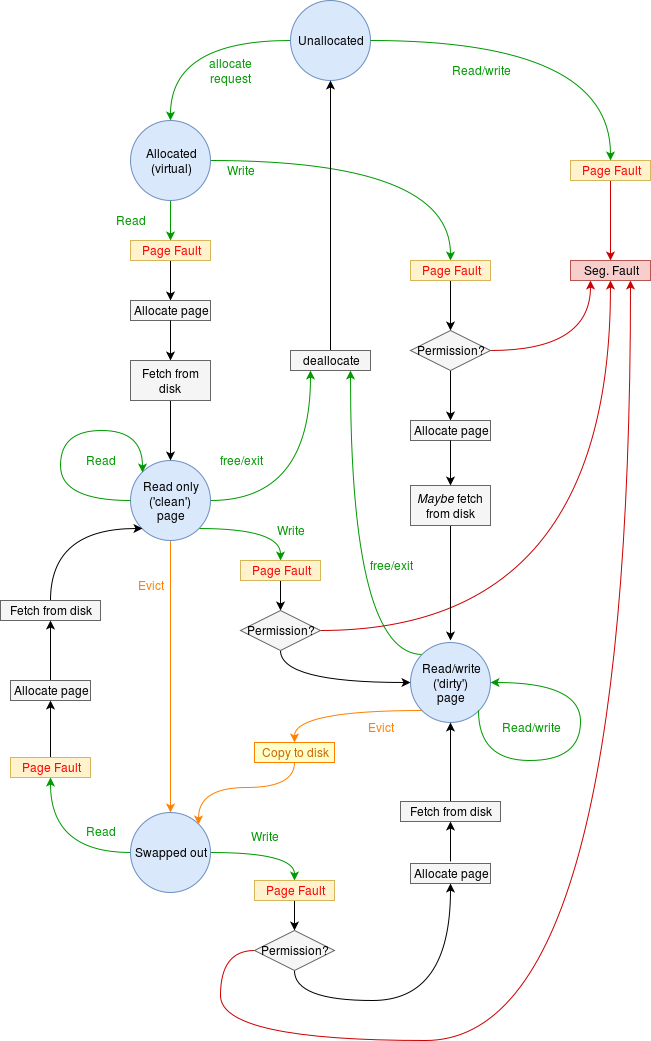

A page fault is a form of a memory fault: a hardware-level exception which causes a form of operating system call. The information about the ‘problem’ is maintained so the processor can recover.

A page fault is caused when a virtual address fails to be translated into a physical address – usually because the page is not present in the physical memory. They are usually recoverable-from.

If the virtual page is marked as not resident, things become more complicated and the operating system needs to intervene. This is triggered by the MMU hardware indicating a page fault. This loading of memory when required is sometimes referred to as “demand paging”.

The exception handler (part of the O.S.) must determine that this is a page fault and not some other form of memory fault. This checks that the virtual address and operation (such as a write) is legitimate.

If this is a genuine page fault the page must now be “swapped in”.

Definition: Memory Paging(Swapping)

Memory paging is the process of modifying the context of some particular memory pages.

The O.S. has to find a page frame for the desired page. In a memory mapped system this can be anywhere in the physical RAM; it may involve evicting an existing page. There are many factors which can be considered when choosing a page to evict.

If the evicted page has been modified then it must be copied back to disk – a time-consuming process.

The chosen physical page is loaded with the appropriate contents from disk. The page tables are modified appropriately.

The figure below is an attempt to show a possible state diagram for a virtual memory page. Each potential page will have its own state.

A page fault has just required that a memory page be evicted so that the urgently needed page can be loaded. Which page should be evicted?

Here are some possible algorithms for choosing:

-

‘Random’ - pick any page. Fairly simple and yet this works reasonably well.

-

‘First-In,First-Out(FIFO)’ - It is one of the simplest page replacement algorithm. The oldest page, which has spent the longest time in memory is chosen and replaced. This algorithm is implemented with the help of a FIFO queue to list the pages in memory. A page is inserted at the rear end of the queue and is replaced at the front of the queue.

-

‘Least Recently Used’ - the page which hasn’t been touched for the longest time. The assumption is that ‘if you haven’t used it recently you probably won’t want it again, soon’. This holds reasonably well for most software.

LRU is often cited as one of the ‘better’ means of predicting the future, but it requires some effort to keep a list of references sorted chronologically; this needs to be supported in hardware as each memory operation (load or store) may move any pave to the back-of-the-queue.

Definition: Page Pinning

Pinning the page is the process to avoid some important pages to be evicted.

There are some pages which should not be evicted – and others which are highly desirable to keep in memory – which contain code critical to the operating system. One example might be an interrupt service routine for interrupts requiring low latency.

Such pages are ‘permanently’ resident and are sometimes referred to as being “pinned”; they are excluded from being chosen for eviction.

3. Memory Swapping

Mapping the memory works okay providing that the sum of the memory used by all current applications does not exceed the size of the installed physical memory. If that happens then some more storage needs to be found.

If the demand on the physical store becomes too great, some pages are copied onto disk to free up some new space. The pages are chosen by a scheduling algorithm; this is the same principle as caching. The process is usually referred to as “paging” or “swapping”.

It is done with a combination of hardware and (operating system) software. the key concepts are probably:

- Memory mapping keeps the application code supplied with memory.

- Memory protection keeps the applications secure and separated.

- The MMU is the hardware which implements all this.

- Paging supports swapping to disk.

4. Memory Protection

The computer’s memory is a resource needed by anything and everything which executes. On the other hand each process wants its own private space which is inaccessible to other processes. This prevents contamination – either accidental or malicious – from one process to another.

It is also important to protect the operating system space from being altered by the user – except in carefully controlled ways which are provided by system calls. This includes:

- operating system code

- operating system data

- memory-mapped peripheral devices

Some protection can be given by memory mapping: if a process has a limited memory map then it can’t ‘see’ memory which isn’t currently ‘mapped in’.

However something (i.e. the operating system) has to be able to do the mapping and any user application has to be able to interact with operating system services.

Thus there is liable to be some memory protection which validates a particular access, using both the requested (virtual) address, the particular action and the processor’s privilege at the time.

If an access of a disallowed type or without adequate privilege is attempted, there will be a hardware exception used to invoke an operating system handler.

The sort of permissions which might be implemented are:

- No access

- Supervisor read-only

- Supervisor read/write

- Read-only

- Read/write by any privilege level

These will be specified in the MMU. Page-based schemes are probably the most common now, so the following description may assume this in places.

5. Memory Management Unit (MMU)

Definition: MMU

A Memory Management Unit (MMU) is the hardware system which performs both virtual memory mapping and checks the current privilege to keep user processes separated from the operating system — and each other.

In addition it helps to prevent caching of ‘volatile’ memory regions (such as areas containing I/O peripherals.

MMU inputs:

- a virtual memory address

- an operation: read/write, maybe a transfer size

- the processor’s privilege information

MMU outputs

- a physical memory address

- cachability (etc.) information

- …or a rejection.

a rejection (memory fault) indicating:

- no physical memory (currently) mapped to the requested page

- illegal operation (e.g. writing to a ‘read only’ area)

- privilege violation (e.g. user tries to get at O.S. space)

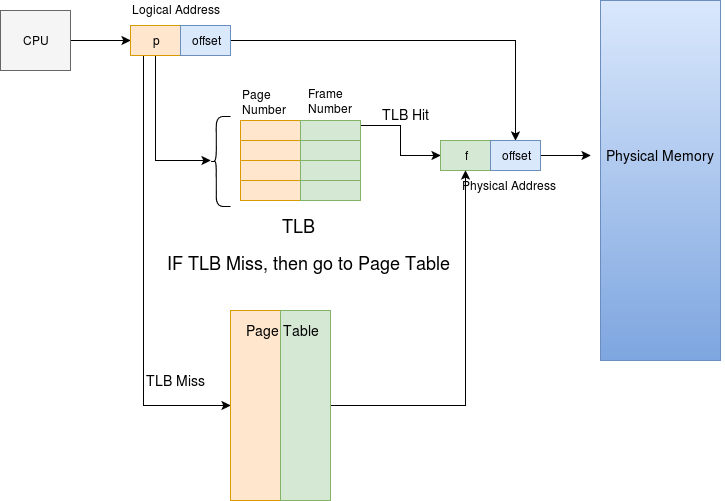

6. Translation Look-aside Buffer (TLB)

Definition: TLB

TLB (Translation Lok-aside Buffer) is a caching buffer which caches a very small portion of page table.

Memory Mapping involves page table look-up. The page tables are large enough to need to be stored in memory. Thus, with a two-level page table scheme every memory access is logically preceded by two more memory reads to translate the virtual address to the physical address.

Slowing down by 200% is not generally acceptable. Thus, when a translation has been done the result is cached, associating the input virtual page address with the resolved physical page. Because there only needs to be one TLB entry per page (not per address) and software typically exhibits locality quite a small TLB can accommodate most software efficiently; this can be fast, specialised hardware.

The TLB holds a recently used set of translations.

- Input: a virtual address (page)

- Outputs: a physical address and some page permissions etc.

Although it is not itself called a ‘cache’ it certainly uses the principle of caching.