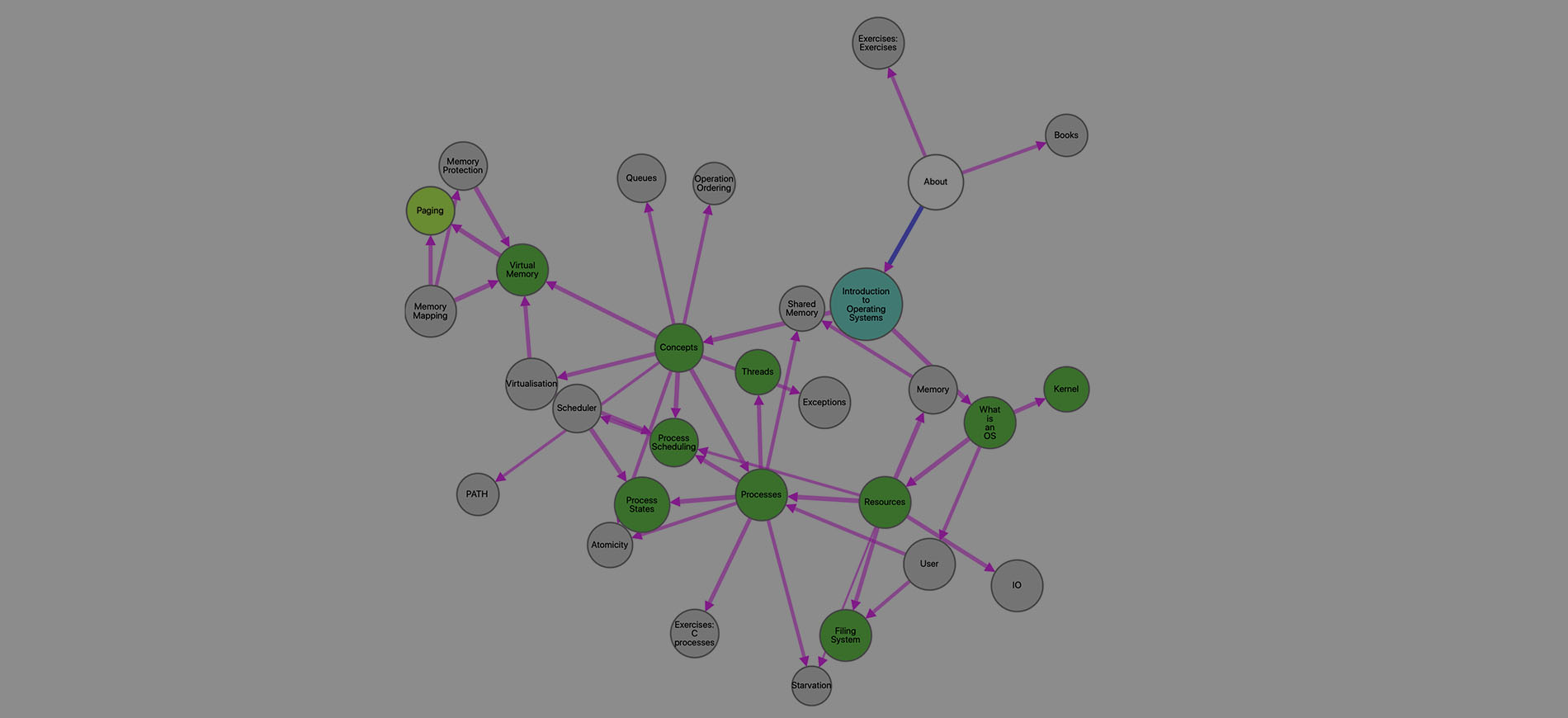

Ch2 Process Management

1. Definition of Process

Definition: Process

A computer program may be defined as the set of instructions which the computer is to follow to perform some computation.

However, when a program executes it needs more information. In practice there are often several attributes associated with this particular, executing copy of a program, such as who ‘owns’ it, which files it is using etc. The executing program, together with this information is typically called a process.

A typical operating system will allow multiple simultaneous processes. Most will allow the processes to be unaware of each other’s presence, unless the processes specifically want to cooperate. Each process has its own context so we may be able to run two or more copies of the same program on the same machine at the same time without them interfering with each other.

Most of the process’ context will be kept in memory. A process will have some address space – possibly contiguous addresses, possibly fragmented into several logical segments – which it can use to hold its instructions and variables. This will not encompass all the memory on the machine.

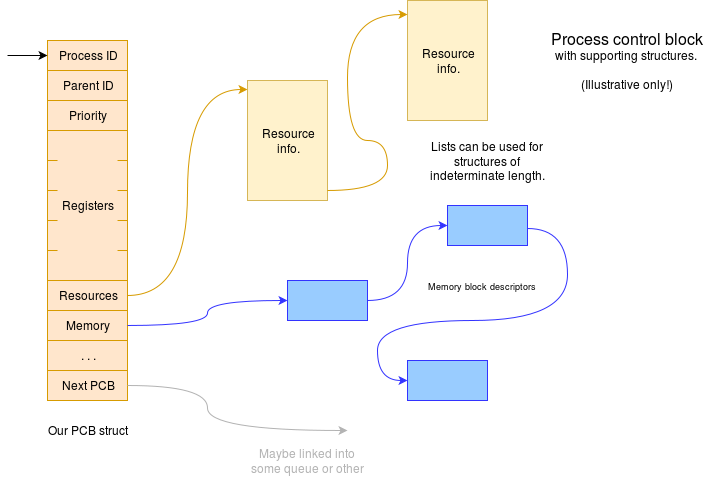

The operating system will also hold some private information about the process, typically in a process control block, which may keep track of the various resources ‘owned’ by this process.

Definition: Context

An executing process will have a particular context. This is the environment in which it operates, and includes its variables and the resources which it ‘owns’.

Register values are part of the process’ context; thus they require saving (in some reserved memory, by the OS) whenever the running process changes.

A process’ full context includes:

- state held within the processor (‘registers’ etc.).

- the memory management page tables.

- a list of resources owned by that process.

- any specific cached information

Definition: PCB (Process Control Block)

The control block is the operating system’s ‘definition’ of a process. It holds information about a process, such as its identifier (‘PID’ in Unix) and its priority.

It will also hold (or point to) the parts of the process’ context which are preserved when the process is not actively running.

The PCB is another example of metadata – in this case describing the process.

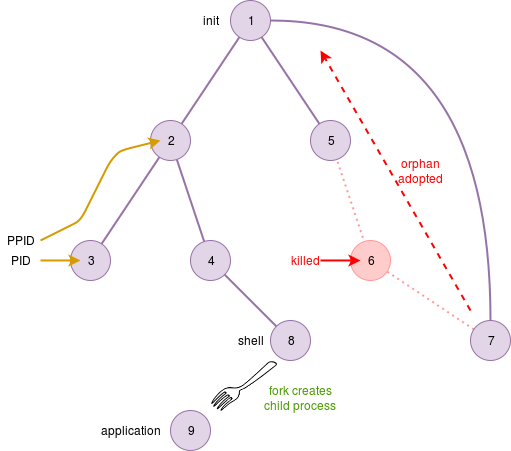

1.1 Unix Process Structure

In Unix-like systems there is a hierarchy of processes, in that each process has (or once had) a parent process.

At boot time the first process (number 0) ‘forks’ the init process before becoming the idle process.

init goes on to create “child” processes. The OS maintains information on the parent (in the process’ PCB).

There is a special relationship in that a parent can keep track of its children and children can always enquire who their parent is.

Definition: fork()

fork() is the means by which a Unix process creates another process. It is a system call which is called once but returns twice – once in the calling process and again in a nearly identical copy of that code (but in a separate process).

Definition: Orphans

If a parent expires before its children, the children are called Orphans, and ‘adopted’ by init.

Definition: Zombies

Zombies are child processes which have terminated but this hasn’t been observed by their (real or adoptive) parent.

The OS retains the ‘dead’ process’ details until the parent synchronises with it. Zombies which persist probably indicate a bug of some sort.

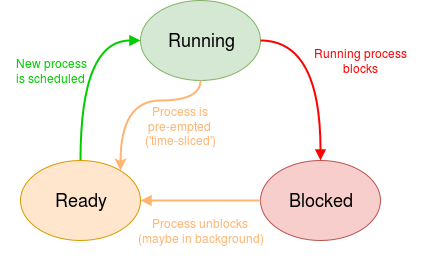

1.2 Process States

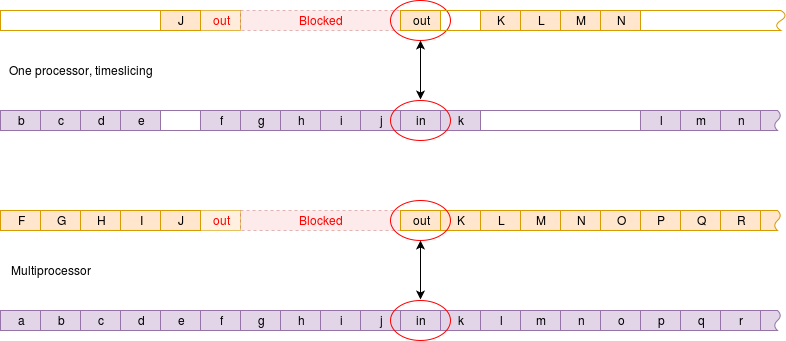

A simple computer has one processor so it can execute one process at any time. You may want to do more than this and a ‘multi-tasking’ operating system provides the illusion that you can via time-slicing.

If there is more than one process to execute, one is chosen and any others are queued waiting for a turn. After some time of execution the executing process may be moved back into the queue so that another process can proceed. The exact basis on which the processes are chosen for running or eviction depends on the particular scheduler employed.

Basically, a process may have the following three kind of states:

- A process which is ready may:

- be scheduled by the OS and set running

- be terminated by some outside influence (e.g. ‘kill’)

- A process which is running may:

- deliberately yield execution (becoming ready)

- terminate itself (job complete)

- be terminated by some outside influence (e.g. ‘kill’)

- A process which is blocked may:

- become unblocked and become ready (e.g. because …)

- I/O has become ready

- time has advanced

- be terminated by some outside influence (e.g. ‘kill’)

- become unblocked and become ready (e.g. because …)

Any number of processes can be ‘Ready’ to be run at a given time. There is therefore a ready queue of processors waiting their turn for scheduling.

Any number of processes can be ‘Blocked’ at a given time. However processes can be blocked for different reasons.

For an communications process, such as a pipe an input or an output should only ever ‘belong’ to a single process, so (at most) one task will block waiting for that. On the other hand, some blocks (e.g. sleep()) may also have a queue of waiting processes.

2 Threads and Multi-Threading

A thread of execution is a single, sequential series of machine instructions.

2.1 Threads

Definition: Thread

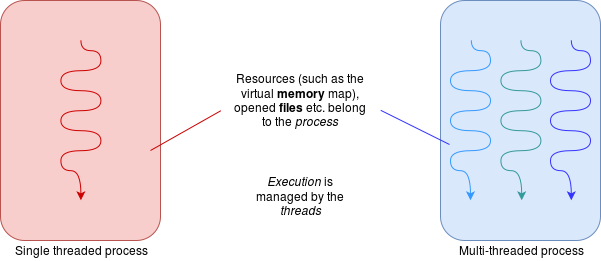

Threads are basically similar to processes. Threads belong within processes. The simple model is to have one thread in each process but any process could have multiple threads.

Threads share most of their context although they will each have some private data space such as processor registers and their own stack.

There are several differences between processes and threads:

- threads within the same process share access to resources such as peripheral devices and files.

- threads within the same process share a virtual memory map.

- switching threads within the same process is considerably cheaper (faster) than switching processes because there is (much) less context to switch.

- it is also faster to create or destroy a thread than to create or destroy a process.

Just like processes, each thread has its own state: running, ready or blocked.

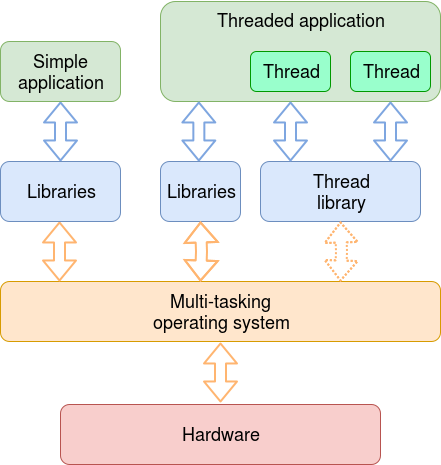

Threads may be managed by the operating system scheduler or, at user level, by a separate scheduler in the application.

Thread management by a user typically allows faster thread switching (no need for (slow) system calls) and the scheduling can be tailored to the application, with more predictable behaviour.

A potential disadvantage in managing threads at user-level is that it requires its own management software for creating, tracking, switching, synchronising, destroying threads. This may be in the form of an imported library.

Thread management by the operating system allows threads to be scheduled in a similar fashion to any process. Context switching (within the same process) can be cheaper than process switching but is still likely to be more expensive than leaving it to the application.

2.2 Multi-Threading

Definition: Milti-Threading

Multi-threading is the term loosely applied both to running multiple threads and multiple processes on a single machine.

it is most usually used when referring to threads which belong to the same program and which cooperate closely.

Multi-threaded code can offer some significant advantages to the programmer:

- enabling simpler source code.

- easier to decompose a problem into semi-independent units which operate in their own way in their own time.

- threading the code will lead to higher performance.

Multi-Threading also has its drawback:

The biggest drawback to multithreading is that it is more difficult to program this way:

‘Traditional’ programming tends to be putting operations into a sequence.

However, in multi-threading programming, when operations are deliberately allowed to happen in an unpredictable order people can get confused.

This, in turn, can lead to subtle faults, which only evidence intermittently, making debugging difficult.

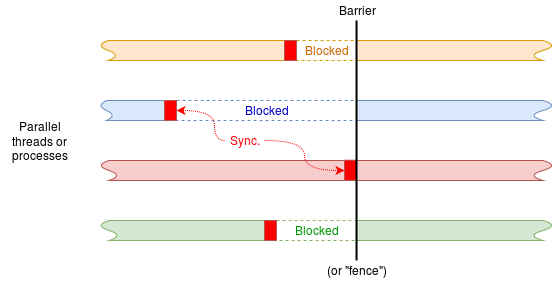

It is necessary to ensure that all dependencies in the code are guaranteed:

i.e. it is certain that one thread has reached a particular point (e.g. the disk has provided the data) before another thread continues past a point of its own.

On the other hand two (or more) threads must not act in a way where they will stop each other from proceeding – a condition known as deadlock.

Definition: Deadlock

Deadlock is a situation where progress cannot be made … ever again.

A process can deadlock if it competes for resources with another process (or processes).

Definition: Starvation

(Resource) starvation is often linked with deadlocks in that it can (potentially) cause progress to stop. However this is really more of a scheduling issue.

A process is ‘starved’ if it can’t get some resource(s) which it needs to proceed. This can be caused by other processes competing for (and winning) the resource.

2.3 Interprocess Communication

multiprocessing is a resource which can be exploited by the programmer and then there is often the need to communicate between processes.

As each process has its own context – deliberately protected from other processes – interprocess communication requires some form of operating system intervention.

There are several major categories to communicate between processes:

-

Shared Memory

If processes or threads share some RAM they can obviously communicate using that. As the processes run asynchronously some form of protocol is usually necessary to ensure data are seen correctly.A simple protocol could be to have an array of data and a Boolean flag. When the flag is FALSE, one process (the “producer”) can write into the array. When it has completed this it can write a TRUE to the flag. It must then wait until the flag is FALSE before writing again.

Conversely, the other process (the “consumer”) waits for the flag to be TRUE before proceeding. It then knows that there is valid data and it can interpret this. When this is complete it can set the flag to FALSE so that more data can be sent.

-

Files

Processes may communicate by altering file-system contents, which are visible to all processes on the system which have the permission to read them.Using the file system is convenient for large quantities of data but the overheads are significant for ‘day-to-day’ operations.

-

Messages

Messages are data ‘blocks’ sent from process to process. They are clearly a means of communicating where there is no memory or file-store in common although messages can be passed on the same machine too.When passing a message, the producer and consumer must coordinate on a one-to-one basis: one message sent, one message received.

It can be important to know whether message passing is synchronised or not.

In a synchronous message passing system to ‘output’ and the ‘input’ operations are compelled to meet.

Whichever arrives at the rendezvous first is blocked until the other arrives. This is typically less efficient in processor time but can give more information/control over process sequencing.

With asynchronous message passing there is the concept of elasticity, where a message queue is maintained so the producer may get some ‘distance’ ahead of the consumer.

This gives greater freedom of operation but less control over timing. The communication is much like a pipe although the messages will usually have some recognised structure.

-

Signals

The term “signal” is used in different ways.-

Wait & signal:

a means of synchronisation where processes (or threads) block and unblock others. -

In Unix (at least) “Signal” is used as a term for asynchronous events. These events are similar in principle to interrupts although they are software generated, mediated by the OS.

-

In terms of interprocess communication, signal calls can request a process to stop or start, indicate anomalies etc. A ‘familiar’ signal example is probably pressing ^C in a shell to interrupt a running process.

-

-

Pipes

A Unix ‘pipe’ – a concept adopted by other operating systems – is a FIFO which can be used to connect processes.

One process is able to write into the FIFO; a (presumably) different process can read them.

Ordering is preserved but there is no data structure per se. -

Barriers

A synchronisation barrier is a means of ensuring no process or thread can cause problems by getting too far ahead of others it is working with. This is not passing data per se, but is still communicating information between processes.Imagine running (say) four processes which all do some tasks with unpredictable timing. Before proceeding further it is important that all the tasks are complete. A barrier will provide this assurance.

3. Process Scheduling & Scheduler

In a multi-tasking operating system not all the processes (tasks) are really running simultaneously; at most the maximum number of running processes equals the number of processor ‘cores’ available.

Definition: Scheduler

The scheduler is the part of an operating system which decides which process(es) to run at any given time.

The algorithm(s) used by a scheduler to pick the ‘next’ process are many and varied and can depend on the particular circumstances.

The approach to scheduling usually varies according to the purpose of the computer system – sometimes referred to as a “processing mode”.

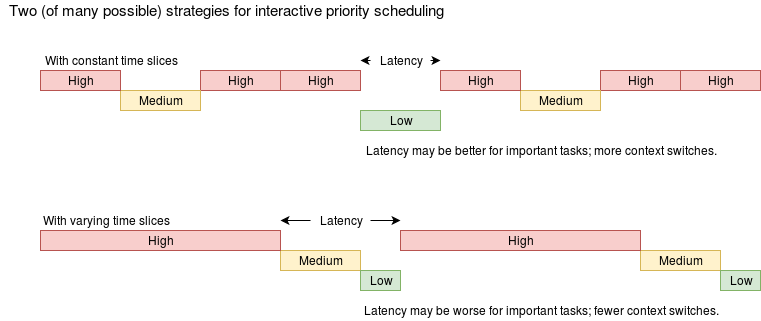

Periodically, the scheduler has to select the next process to run. Time-slicing with a simple round-robin algorithm would give an equal share of processor time to all processes which are not blocked. This can be too simplistic to be useful. It is often useful to be able to assign priority to processes so that some are favoured over others.

Definition: Process Priority

Process Priority is a value set by the user or OS based on the type of the process reflecting its urgency or importance.

A process’ priority may be set by the user (or the system) in various ways. It may be constant or calculated dynamically.

Priority can be applied in different ways too. In a real-time system it probably dictates that the highest priority ‘ready’ process runs whilst it can.

In an interactive system, this approach could prevent lower priority processes proceeding at all, so the strategy may be different.

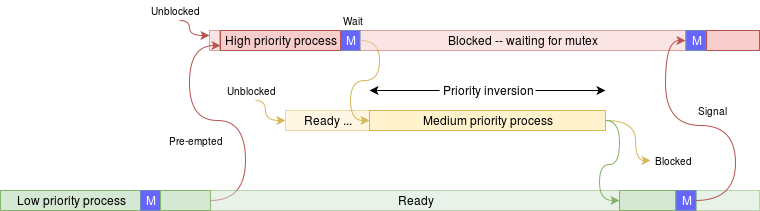

Definition: Priority Inversion

A “priority inversion” is a circumstance where a high priority task is prevented from running by a lower priority task.

There are following possible scenarios for this to happen:

-

A low priority task acquires a mutex.

-

A high priority task pre-empts, tries for the same mutex and blocks.

-

Before the low priority task can release the mutex a medium priority task occupies the processor.

The high priority task is suspended until the low priority task frees the mutex. Normally this would happen quickly but the low priority task isn’t allowed the chance. The medium priority task – which would normally be pre-empted – hogs the urgently needed resource.

3.1 Interactive processing

This will be a familiar mode where the user constantly interacts with the computer which, nevertheless, occasionally has some time-consuming tasks.

Scheduling is arranged to give reasonable responsiveness to various jobs as the user changes focus.

In interactive systems a common approach is “round robin” scheduling. This is an attempt to give all processes equal ‘turns’ by taking the next process from the front of a FIFO queue whilst appending a de-scheduled process to the back.

This is most obviously applicable when time-slicing, (or cooperative ‘yielding’) when a running process is de-scheduled without being blocked.

The scheduler needs to try to be ‘fair’ to avoid starving any process of a share of processor time, although the details might be influenced by the process’ priority.

3.2 Real-time processing

Real-time computing requires a guaranteed response with a certain, maximum latency. Contrary to some opinions, this does not make it fast: in fact it is essential that the processor is regularly becoming idle because if it is not it means it hasn’t completed everything it needed to do in time.

Real-time schedulers typically rely heavily on priority, with some processes being identified as more urgent than others (i.e. low latency is required); these will typically be run in preference to lower priority (but still time-constrained) jobs.

Real-time tasks are sometimes (somewhat arbitrarily) divided between “hard” and “soft” constraints:

A hard real-time task is one where failure to meet a constraint leads to a system failure.

A soft real-time task could be summarised as one where undue delay leads to annoyance.

3.3 Batch processing

Batch scheduling picks a particular job and completes that before proceeding to the next. It is therefore not responsive to interactions but is efficient at processing. It is often appropriate for big data processing jobs.

A common approach in batch jobs is shortest job first. A simple analysis will show that this finishes more jobs, sooner.