Ch3 File Management

A typical computer might have a number of ‘levels’ of storage. The machine’s hardware view is usually something like:

- Processor registers

- Primary memory – chiefly

RAM - Secondary storage – typically

disks - Network – not really part of the computer but a source of data nevertheless

File-store is provided to supply the following requirements:

- Large storage capacity

- Data persistence

- Inter-process communication

1. Filing System

1.1 Filing System

Definition: Filing System

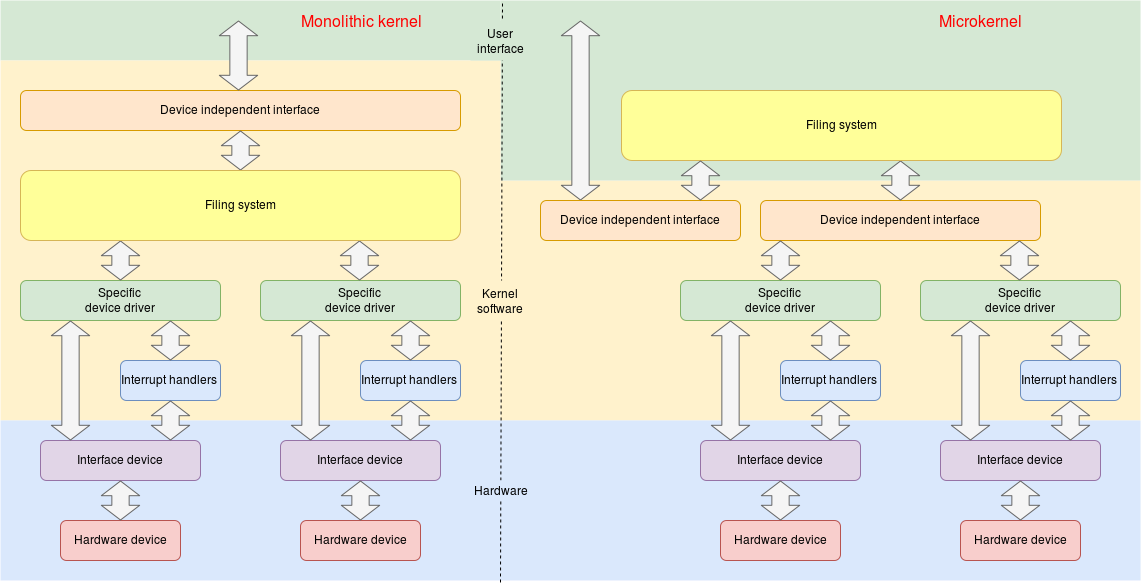

The filing system lives between the user applications – which want to handle files and the disk (or other) device drivers which move blocks of data to and from.

The Filing System is clearly a part of the OS, since all processes should see the same files. In a layered model the filing system is quite a high-level OS layer. In a microkernel it may well be run (by the OS) in user mode.

The simplest file-stores are ‘flat’: i.e. there is one place where all the files are kept.

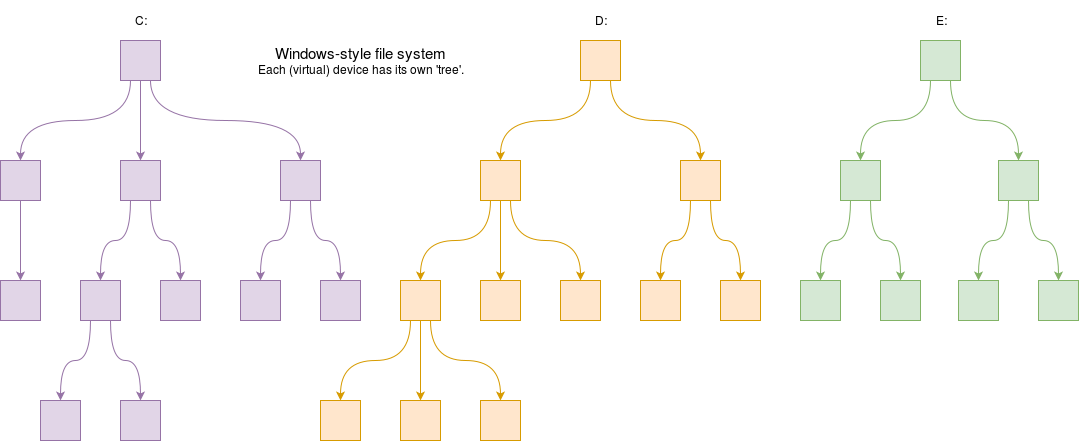

Another mechanism is to identify separate devices, such as “A:” or “C:” In modern systems these may be virtual rather than physically separate devices. (Think about Windows’s disk partitioning!)

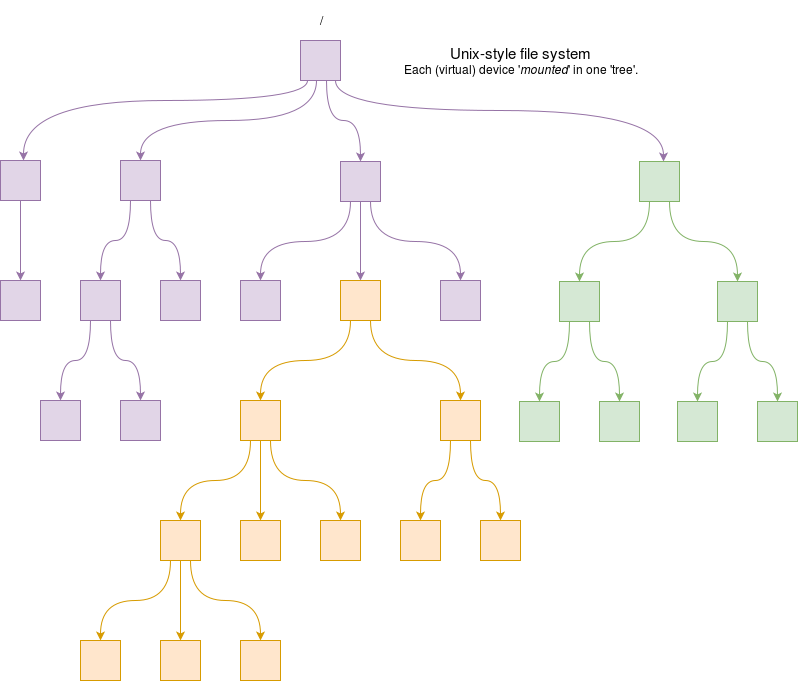

A modern file-store is most likely to be hierarchical with a tree-like structure of arbitrary depth. Each tree has a single ‘root’ which branches repeatedly. Windows systems still retain separate “roots” for each (virtual) device though.

Unix (on the other hand) file-store mounts devices in a single ‘tree’, so different disks (and other stuff) appear as branches.

- Branching points are directories – sometimes now called “folders” but we shall stick to “directories” which is more usual in the O.S. context.

- A directory can branch zero (empty) or more ways; there is no particular logical limit. Terminal points on the tree are files, containing data.

Every Unix directory contains at least two files: these are “.” and “..”. Thus the parent directory is explicitly specified.

Filing Systems have the following typical common characteristics:

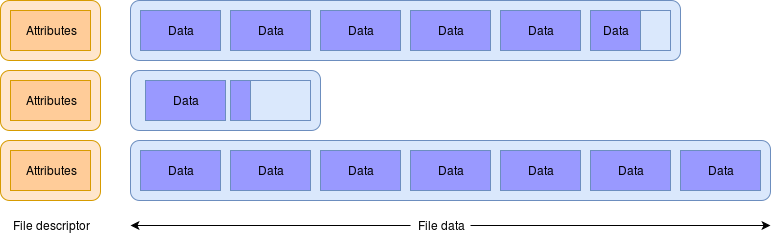

- Allocation is done in blocks; a file occupies a set of whole blocks (although the last one may not be completely full).

- Reflects the way data is stored on disks (and other media).

- Will hold $2N$ bytes: somewhere around the $1 \text{KiB}$ size.

- Reduces the number of items to ‘address’.

- Not a completely efficient use of space.

- There will be some blocks used for data and some for the system organisation.

files can vary in number and length. If files are laid out on a disk as contiguous blocks, it will suffers particularly if/when an existing file is extended in length. Most systems will therefore allow the file block placement to be fragmented rather than contiguous, with some way of indexing the blocks so that each file specifies its own blocks in the correct order.

Despite the ability to lay out blocks at ‘random’, file systems still assume that they will be using magnetic disks (or similar) which are not truly random access devices: it is faster to read successive blocks than scattered ones. Hence the fragmentation of files will cause some slowing down.

Sometimes a disk will be deliberately partitioned to assist with this. Various utility binary files may be kept in a separate partition from the user files which change and are reorganised frequently. It is changing a partition’s contents which leads to fragmentation, so this means often-wanted files can be kept tidy and not suffer a slow-down.

1.2 Links

Definition: Link

A Link is an alias for a file. it is added for having a file in more than one place while not copying it.

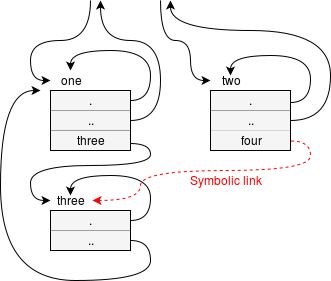

Adding links can cause complications. The structure ceases to be a simple tree and becomes a directed graph.

Particularly, it is undesirable to form cycles in this graph: recursive searches would never reach the ‘bottom’ of the structure(since it loop inside the cycle forever). A particular system way therefore not allow such links to be created.

In Unix, at least, there is more than one way of building a link:

- Symbolic links

A symbolic (or ‘soft’) link is a special form of file which is simply a form of pointer to another file. The other file could be a directory.

A symbolic link, being an alias for an object, does not have to link to anything real. - Hard links When a hard link is created it is a directory entry which links to the i-node – to the file itself, not another name. The link is the file.

Note:

- “Deleting a file” which has multiple links will not actually delete the data.

- Deleting a file when that is the only link would leave the i-node isolated, at this point it becomes available for reuse.

2. File

2.1 File

Definition: File

A file is the basic storage unit in a filing system. They are large but slow to access (relative to main memory structures), possibly accessible by many users and processes, and permanent.

Each file comprises a standard set of file attributes (e.g. the file size) and a variable number of blocks/“clusters” which contain the data. It is normal (but not compulsory) to keep only one type of data in each file.

The data may be structured into records, either by the filing system itself or through user preference.

Most modern file systems leave any structuring to the user and regard the body of the file as a large array of (usually) bytes.

Some operating systems may allow the virtual mapping of a file into the address space for added convenience.

When reading (or writing) a file there is an associated position, this is not part of the file though but is maintained by the access process. It is possible to have multiple processes reading the same file at different places simultaneously.

A file will typically have some type part of which may be maintained by the file system and some from the user’s knowledge. Each file has some unique identifier but the user will usually have a human-readable name by which it can be identified. This “file name” may or may not be part of the file’s attributes.

2.2 File Types

The file-store holds a large number of files which represent numerous different things. There are various ways in which the file type can be classified.

Unix, Windows etc. show various filenames in a directory (“folder”) which are not necessarily immediately distinguishable to the user as ‘regular’ files or subdirectories. This is an important distinction for the filing system itself and the information is kept within the file attributes.

File browsers and similar tools use the following ways to deduce what a file actually contains:

-

Filesystem tests use the attribute information available.

-

“Magic” tests look for a “magic number” at a known place in the file. (e.g. how to distinguish between jpg and png?)

This is a useful way to guess what a file type is – it is, of course, not 100% reliable. -

Language tests are applied if a file has not been determined yet to see if it looks like text (which bytes are used, which are not) and then some keywords may be tried to see if it seems to be the source code for a particular compiler (for example). This, too, is not 100% reliable.

It is common for users to imply the type of a file with its name, often with a suffix extension . For example, a ‘text’ file may have a name like file.txt.

In some systems this extension was logically separate from the file-name and formed part of the metadata.

On common modern systems (Unix, Windows) this is not the case and it is there purely for human convenience.

2.3 File Attributes & Permissions

2.3.1 File Attributes & Descriptor

Definition: File Attributes

The associated metadata of a file containing information about it is called file attribute.

Note:

-

this is ‘permanent’ information about the file; it is not the same as the file descriptor which is the information about a file in use by a particular process.

-

file attributes often contain file permissions. File permission limit the operation of certain user groups to the file, which provides some simple protections.

-

In a multi-user system it is useful to know who ‘owns’ which file. An associated, unique identifier can provide this information. (The user’s name can be looked-up from this if necessary.)

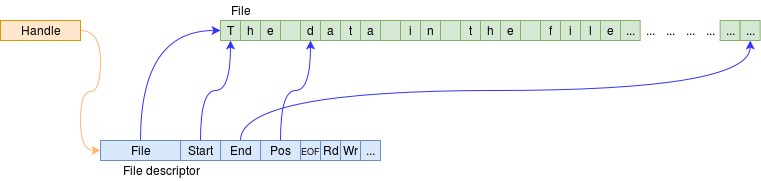

Definition: File Descriptor

The descriptor will be created when a file is opened and is associated with a particular file within a particular process. It is used for immediate file access.

It will hold information such as:

- the access permissions.

- the current position (index) in the file.

- the error status.

- control flags.

Like the file attributes, a file descriptor holds some metadata about a file. However these are not the same thing:

- The file attributes are ‘permanent’, in that they exist with the file; the file descriptor only exists whilst the file is in use.

- There is exactly one set of file attributes per file; there can be several file descriptors for the same file if it has been opened multiple times concurrently. Each descriptor will have (for example) its own file position.

2.3.2 File Permissions

Definition: File Permissions

File Permission is a form of access control for protecting files from unwanted access or modifications, which provides some simple protections. Most file systems include some form of access control.

In the simple case, this could support multiple users of a system so that each user’s files were private. On its own, this would be rather primitive because it would imply that every user needed a separate copy of every application program etc.

Unix-like systems typically have three classes of file access permission which, combined with other information, provide reasonably flexible access control. These are part of a file’s attributes. The relevant information is:

- The file’s owner (

UID). - The file’s group (

GID). - The access permissions in terms of permitted {read, write, execute} for

- the owner

- members of the group

- any system user

For a regular file:

- read (

R) permission allows the appropriate clients to see the content of the file. - write (

W) permission allows the appropriate clients to change the content of the file. - execute (

X) permission allows the appropriate clients run the file as code.- This includes execution of a binary file and a text file in the case of a shell script.

Permissions for a directory are similar although:

- execute permission allows the user to follow the links in a directory – e.g. to sub directories.

It is possible to follow through an ‘executable’ directory even if it is not readable.

Groups are defined in a system file, which itself should only be writeable by ‘root’ to keep the system secure.

They allow a group of users access to particular space so they can work together whilst excluding the ‘general public’.

File permissions have a similar function to memory access permissions, providing not only security against intrusion but also safety against accident. The usual general applications binaries will probably be owned by root – or some other non-usual UID – and not be writeable by anyone else, thus they can be read and executed but not deleted.

Write-protecting files is often a good safety strategy. Similarly, files such as photographs can be set so no one will (successfully) attempt to execute them!

2.3.3 UMask & ACL

Definition: UMask

In Unix(-like) file systems there is a default set of file permissions for files created by each process. This is called umask.

Definition: Access Control Lists (ACL)

A more sophisticated means of controlling file (and other) permissions is an Access Control List (ACL). Such a list contains entries which specify the permissions of file access for each file for each user, allowing more selective permission control than single groups. The list is referenced by the filing system to allow or deny access to that file.

Access control may offer other features, such as logging access to a file for audit and security purposes. It can then be possible to track everyone looked at or changed a file and when. This is usually only important when dealing with sensitive data.

2.4 File Access

Users usually identify files with filenames or a path to a file. The name is a string which is an inconvenient item for the OS to handle. It is therefore usual to associate an abstract handle leading to a file descriptor of a file which is in use.

Exactly what the handle is does not usually matter to a user. It is just something with which the user can identify a particular file.

This gives access to the file descriptor via various ‘method’ calls:

The first thing to do is open a file. This will then fetch a block of the file into a buffer which prevents a disk access on every Read call to save resources(Caching again!).

Reads are then made from the buffer, which is refilled when necessary. Read operations can continue until the End Of File (EOF), a point which prevents further reading. The file can be closed at any time.

Other things may be mapped to ‘look like’ files and the same, device independent interface. These include:

- Streams

- Pipes

- Devices among other things.

The description below covers the ‘classic’ access operations:

-

Open

It’s necessary to “open” a file in order to obtain a file handle.

This system call will assign a handle to the required filename/path for the relevant process (the last time this string is needed), check and set up the appropriate permissions and reset the file’s (internal position) pointer to the start (or end, if “appending”). It can fail and thus signal various errors. -

Close

When a file is finished with it should be “closed”. This may – for example – be needed before another process can write to that file.Closing the file will also flush any remaining buffered data to the file itself.

The O.S. may close any remaining open files a process owns when the process terminates, but it is good practice to tidy up as a matter of course.

-

Reading and Writing

For efficiently reducing the number of system calls needed it is usual to read or write blocks of data.Typical read or write operations move a contiguous number of bytes or words from the current position in a file to a specified memory buffer, or vice versa. The position in the file is advanced by the same distance because file operations are, mostly assumed to be serial.

-

Seeking

It is possible to apply some ‘random access’ to files in the same way as the computer can to its memory, although the process is somewhat more expensive.Rather than simply using an address, system calls are used to read or write the position index (which typically post-increments after each data read/write operation, for convenience).

This treats the file as a (large) array. There is a question as to what the elements of the array actually are. Sometimes files may have inherent record structures. More usually they are regarded as bytes and it is up to the application to apply the organisation. Unix files are bytes.

An alternative approach in some operating systems is the ability to map a file (or part of a file) into (virtual) address space. It can then be treated as (for example) an array. This can be convenient if a lot of ‘random’ access is required.

-

EOF

Unlike an array in memory – which has a predetermined size – a file can be of (effectively) any length. When treated as a stream it is rather useful to know if/when the end has been reached. This can be indicated with an End Of File marker.One approach is to reserve a particular control character for this (^Z a.k.a. SUB has been used in MS-DOS, Windows and other systems). This is fine for printable text; the problem is, of course, there needs to be a way of sending any value in a binary file.

Unix systems have an EOF status which can be read by a feof() call from C, for example; if characters are read beyond the end of a file then the value EOF is returned; this is an ‘out of band’ character (usually -1) whereas characters are actually returned as integers, so 257 different return values are possible.

EOF status could also be tracked from the file size.

Definition: Stream

A Stream is a serial flow of data. It is not the same as a file: files can be addressed in a ‘random’ manner. However, files are not infrequently read or written as serial streams.

In this case, the stream is an unstructured, serial succession of bytes. Input from the stream will give the next byte – if and when there is one – and the byte is removed from the input sequence in the process. Output to a stream will output – assuming no ‘back-pressure’ from something (such as writing a file) being slow further downstream; again the byte is then ‘gone’.

I/O devices can also be treated as streams, such as keyboards.

All Unix processes are provided with three standard streams:

- Standard input (

stdin) – usually defaults to keyboard. - Standard output (

stdout) – usually defaults to display. - Standard error (

stderr) – usually also defaults to display.

Processes can ‘get’ and ‘put’ characters to these streams in various ways. They are typically the default source/sink of input/output in system applications.

Definition: Pipes

In Unix (and similar operating systems) a ‘pipe’ is a means of passing a serial stream of data from one process to another.

A pipe is a FIFO queue with two interfaces – one for inserting data and one for removing them.

Pipes can be created to link processes. A typical use for pipes is as a redirection of standard I/O streams, often invoked from a shell.

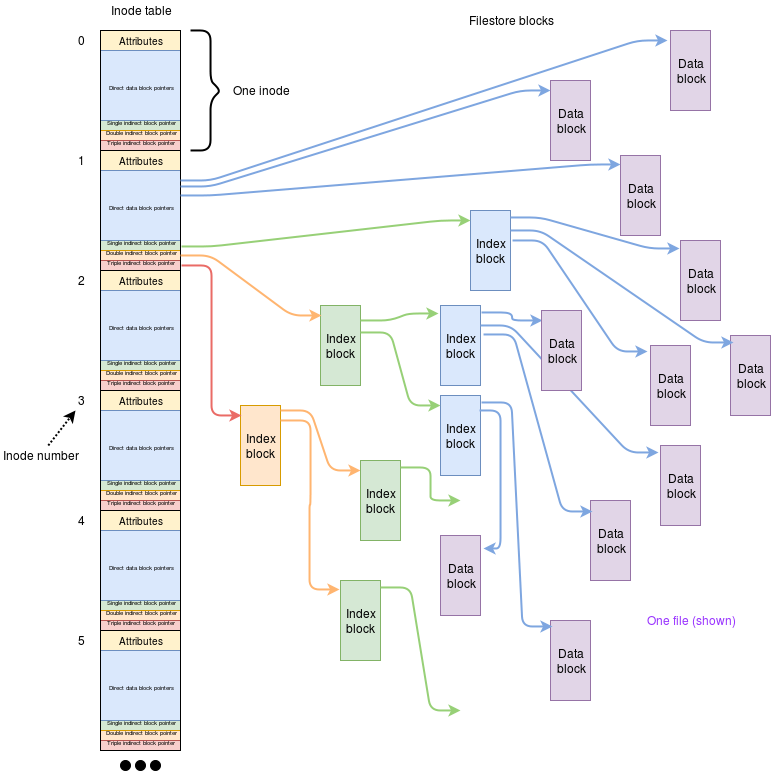

2.5 I-nodes

Definition: I-nodes

Used in Unix systems, an i-node is a structure containing some file attributes and an array of pointers to blocks used by a particular file.

an i-node is quite small (and a fixed size) thus it can only point to a limited number of blocks. This could limit the maximum file size rather seriously.

However, not all the blocks need to contain data. A block can, instead, be filled with pointers to other blocks. This allows considerable expansion. If that is not sufficient the ‘other blocks’ can also be pointers themselves. Some known convention can be used to determine the meaning of each item.